#1It’s surprising how the most of the time, what seems like a fresh and interesting beginning gradually sags down to distressing boredom. When I had stepped into Bombay a year ago, I was captivated by the sheer brilliance of bustling activity at Churchgate station. Then, it had seemed as though I was living life’s best. It isn’t often and infact, not for long, that life gleams with such optimism.

This is how it all began. Bright sunny mornings, chaotically colourful, scurrying, ‘me-my business’ people all over, and me, the solitary walker with earphones plugged on, from the moment I stepped out of my hostel through the 20 minute walk towards the station – we were all a part of this huge machinery that was Bombay, moving in and out, in sync, like nuts, bolts and axles of a system that moved tirelessly 24 X 7. But the bratty Time taught me a lesson – the lesson that there is something really catastrophic about a life that offers very little impedance. Monotony could sometimes make you so weak and could leave you defenseless against change, unless you have the courage to overcome it. Routine is an illusory trap!

My thinking process usually writes itself bold and clear on my face. I very much guess that I could have been an object of muse for co-passengers in the 9.30 local that I usually took to reach office. My mind races back to that particular Tuesday, last April. My disc-man was entertaining me as ever and it was Yanni’s Nostalgia filling the moment with a serenity not experienced for a while. And no big guesses, yeah, I was lost in thought. I could feel the coolers that I had pulled back over my head. New ones. Fast track, light brown, flimsy plastic – 5000 bucks. I was wondering how long its charm would last, for the previous purchase, a pair of high-heeled sandals pleased its owner for only two months. And then the owner settled down for a pair of bare flats, the next best approximation to bathroom slippers (well, these were ethnically designed ones.)

“What am I doing here?” I thought. Mom and Dad wanted me to do an engineering degree and a techy post grad. But I had fought and shouted my lungs out crying a big No. Thankfully, Shridhar Uncle, dad’s brother was big support. I did my graduation in business administration and since my heart lay in writing, went on to do a post graduation in journalism and jumped into the media world. The rest remains history.

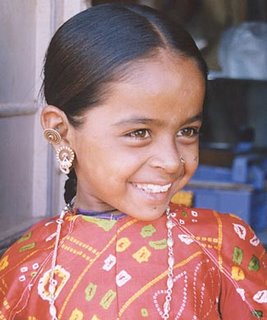

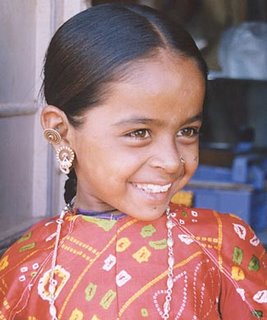

I closed my eyes and scenes reeled inside my head when I felt that light tap on my thigh; the tap that was to steer my destiny on a different course. The train had stopped at Charni Road. I opened my eyes and there stood a young girl, wearing the costliest asset she could carry – a bright, wide smile.

“Hmm?” I murmured, still not off my inner world that was ringing with a thousand, unanswered questions.

“Didi, choodi logey?”

“Hmm..No..uh, No..,” I shook my head confused.

“Please didi, yeh pink colour aapke dress key saath bahut achaa dhikegaa, please..”

If not for anything else, I was so pleased by her smile and her brown eyes.

I nodded. “Teek hai, woh pink waala dhikaao”

She helped me try them on. I decided to buy them.

“Kitna bolo?”

“Didi pandraah,” she replied breathlessly. Come on, she had after all made business for the day.

She surveyed me with her large eyes as I dug into my bag for my wallet.

“Oh oh..,” I said holding a 500 rupee note, “No change..” I shrugged.

Her face fell instantly. Hopes had crashed. May be she had dreamt of having 'dho roti aur dal' that night. I felt pangs of guilt within. Oh, how I had ruined and killed small dreams..

“Teek hai, I will buy it from you tomorrow,” I promised. She nodded and was off to woo other buyers in the ladies coach.

The night meant hectic work. A survey report was due for submission, end of week and I sat on my bed, pouring over a hundred printouts and trying to gather sense and of course, I was biting nails, munching chips, drinking pepsi (did I say that was my dinner or rather I had skipped dinner?) and on top of everything, feeling terribly, terribly bored. The RJ from some FM station chattered endlessly and at one point, I was tuning in and out of stations as a matter of addiction. Search, search, search, for something better. Well, what was I

actually searching for? I seriously wished I could gulp down glasses of whisky and lie frothing like a careless drunk because,

only because I could chase boredom away for a while. But, work beckoned. I was turning out the front page story for the weekend issue. I couldn’t slip. It’s a mistake that would cost me my reputation. What would people think of me?

The next morning in the train, she stood before me. I wonder how she remembered my face from among the sea of faces that she would have seen the previous day. Secretly, I felt proud but it was a sense of shame that overrode pride for I had completely forgotten a promise that I had made to a small girl. “Hi,” I said and smiled at her.

“Didi, woh pink choodiyan aaj loge?” she asked anxiously.

“Yes,” I nodded and she packed it up in a jiffy.

“Here,” I said, handing her the money, “Kya naam hai tumhara?”

“Muniya,” she said, “Munni..”

“Oh, sweet name,” I smiled, and she blushed.

My eyes followed her as she moved about the coach throwing glances at all ‘working women’. May be she thought, all of them were her sorts. Even she was working, after all, only that she was a girl. On her way back, she smiled at me again. She took me by surprise when she came and settled down in that empty seat next to mine.

“Didi, aapka naam kya hai?”

“Sindu”

“Aap kahaan pe uthroge?”

I paused. “Why?” I asked.

“Bas, aise hee,” she said in a breeze.

“Elphinston,” I replied.

“I get down at Dadar”, she told me and explained complex equations of switching trains to do her business. I listened patiently as she rattled on to explain how she had hopped into this whole thing fairly recently.

Did she speak to somebody else on the same train or may be some other train, the way she had been speaking to me in the last few days? I was dumbly curious. Why did I seek that reassurance? Why did she have to tell me and move me by her stories? Did she want money? I was researching intentions. The next day she put me to shame.

She had passed around her box of bangles and quietly came over to me.

“Good Morning,” she said, briskly saluting, the way I had taught her. I smiled and signaled her to sit next to me. Munni was a finely dressed business girl. So what if she didn’t have money, she still looked neat, smart and bright.

“Tho, baath kya hai aaj?” I questioned. She smiled shyly and put down her head.

“Kya hai?” I repeated.

“Didi, woh..” she pointed at my disc-man, “mein sunoon?”

I burst out laughing.

Yeah, yeah, why not? I put on Kajraa re and had to literally pump all my energy in holding her from dancing. How could she be so innocent? I wondered, for she was most willing to throw a cherubic smile at the earliest and put anyone to ease. I envied her.

I had to nudge her back to reality, halfway through the song, for some customer needed attention. Before she left, I thrust a 50 rupee note in her hand. She moved away dismayed. “Nahin didi, nahin chaahiye..aap chaahiye to choodi le lo..” she said sternly and was off.

#2Munni’s life was the playhouse of a devil – the devil called poverty. Her parents had seven children including her. The first five were girls, the last two boys; Munni was the fifth one and the last child was barely a year old. Let me recall names that she had told me with such vivacious enthusiasm. Heera, Moti, Chandni, Piyu, Muniya, Sanju and Bolu. May be her parents decided to give them all at least rich names, if not anything else. Her father was a watchman somewhere and often returned home drunk. Her mother, well, she just existed, a child producing machine.

My report for the week was finally taking shape. The survey indicated that consumerism was on the rise in urban India. Plastic money was booming – everywhere, everyone wanted to swipe their cards; Why not, when every other business entity was ready to woo its customers with attractive gifts, offers and freebies (of course with a strict, “*conditions apply” tag attached). Four out of every five in the urban working class held a credit or debit card or both. Malls, multiplexes and eat outs remained most frequented places. An urban man and woman on an average would spend close to a thousand a weekend, in entertaining himself or herself. While men usually spent it at bars, eat outs, gadgets and movies, women let out their share into clothes, jewelry and accessories. Yes, you could count me in along with those women. Markets were booming, industries were thriving, and the Indian economy was registering an awesomely positive GDP growth. All was well. But why did slums still exist in Bombay and everywhere else in the country?

I was surprised why Munni never went to school. When I asked her that, she shrugged and replied, “Ladkiyaan school nahin jaathey..” I was stumped. Was that the idea instilled in her – that, girls in her family were never meant to go to school? None of her sisters knew to read a word, only Sanju saw something of a school. Harsh yet real inequality! And why did she start selling bangles? “To supplement the grossly low family income,” she reasoned. Once she almost whispered a business secret. That Saturdays and Sundays, women wanted to buy more bangles. “Holiday mood,” she classified. What a striking similarity between the world of malls and that of a small bangle seller!

Once the report was published, I got a breather. I had a vague idea about something I wanted to do, but wasn’t sure. The next day, I caught Munni, five minutes before I had to get down. “Munni, I want to come and see your home,” and she almost jumped, out of fear or excitement, I knew not. “Kyon?” she asked, bewildered. “Bas, aise hee,” I beamed. She was quick enough to reconcile. We decided we would meet up Friday afternoon at Dadar and move to her place.

I am sure I looked like the firangi memsaab, with my coolers, scribbling pad, handy cam and all that equipment that I was carrying. Munni seemed excited for my arrival and disturbed at what seemed like a threatening and definitely foreign demeanor. I felt like an alien in the territory of the poor. Curious, anxious eyes of men, women and children scanned me from top to bottom. I gestured to Munni to pick up those biscuit packets with me and give it to all the children. If I called that a mad rush, it would be an understatement.

A frail woman invited me into a hut that was bare land with an equally frail roofing on top. People peered into the hut as Munni’s mother made a vain attempt to shoo them away with her weak hands. Munni introduced her sisters and the story of Miraben, Munni’s mother and her narration went straight into the handy cam. I had some tea in a dirty looking glass.

I returned to my hostel and spent the weekend browsing through what I had scribbled and recorded. Miraben was married away when she was thirteen and had her first child when she was barely sixteen. She had seven children with two miscarriages in between and finally got herself operated. Her husband was nowhere to be seen. “Don’t talk about that man,” she screamed.

She was almost wailing in the recording. Her first daughter eloped with a man from another caste and was hence, cast away and disowned by the people of her clan. She hadn’t seen her daughter in three years, she complained. Munni threw an apologetic look at me. She was may be repenting why she ever got me there. I smiled in assurance at the sweetly understanding child, “am ok..”

My usual weekend Marine drive walks were now replaced by visits to Munni’s slum. The place looked unmanageable and petrifying during monsoons. There weren’t well built sanitary and drainage systems and whatever was there of it, looked awful. As if humans weren’t enough, dogs and other animals huddled together inside huts. I got to hear Sarada’s story of how her son died of malnutrition and so many other heart rending tales of Munni’s neighbours.

#3Immediately following that, somebody at office made a big hue and cry about missing his name in the byline list, for no big deal a contribution. What did people want? The downpours were getting heavier. The next day I didn’t see Munni in the train. What could be wrong? Another day and yet another, she wasn’t to be seen.

May be she was just another acquaintance but why was I bothering so much about her? Somehow I grew restless. That evening, I visited her so called house and her mother reported that Munni was down with jaundice. I had to wait for the weekend to arrive. I visited her at the Government hospital.

She had grown weak and sick. But the eyes and smile were still intact. “Don’t worry, you will be back in action soon,” I told her. It was as though I was feeding her morsels of hope that she was desperate to claim; Emotional food for the soul akin to dry crumbs that would tease the tongue like a heavenly delight. She was poorer by food, by money; poorer by solace, by choice.

“Everything would be okay,” I had told her and she believed me. What was I doing? Wasn’t I just making a passing remark when I consciously knew that my comforting words weren’t practically going to make any difference to her?

More often than not, I am led to believe that I am a fickle minded fool. Spending days together visiting those huge slums left me with a strange sense of bereavement. Could I ever decide for sure what I felt for the likes of such people? It is tough to classify the feeling. Was that pity, a silly feeling covering up an unwillingness to take up responsibility or rather indifference, an irrational and unpardonable selfishness to avoid being a part of gnawing misery? Could I by some personal means, pull off the entire dirt called poverty that rode on the souls of so many such people?

I wanted a way out before the thoughts inside my head grew stale and clogged my mind. A friend of mine once said that out of confusion, clarity is born. For days together I pondered for an answer and it wouldn’t arrive easily for the simple reason that I feared change. I was close to making a decision but that meant I had to forego the boring yet secure and cozy monotony of the life that I had settled into.

It meant I had to travel, see unseen and unheard of villages, realize without any inhibitions the implications of a living condition called poverty. And I knew I wouldn’t understand it unless I whole heartedly embraced the flaws and pitfalls that came with that way of life. It needed a transition from the wholesome to the hollow and it wasn’t easy.

I read and re-read my diary entries and viewed the unedited documentary on my handy cam, and I knew I was almost at it. I knew not how far it would reach, but I would definitely make the attempt.

I decided to write that book and film that documentary.

But, Where do I begin?

I looked up my address book. Shridhar Harihar, Executive Editor, ColorMagic Media.

I applied for a sabbatical at my workplace.